Projects

The Death Penalty in North Carolina

The death penalty in North Carolina, as elsewhere in the United States, provides a steady drip of controversy. The state has been under a de facto moratorium since 2006, when a disagreement over the presence of doctors at lethal injections halted executions. In 2007, the process was further arrested by inmates who filed suit over lethal injection, claiming the drug cocktail would impose a cruel and unusual punishment on them. Then in 2009 came the Racial Justice Act, which allowed prisoners under sentence of death to use statistical information about racial bias to request commutation. Most death row inmates filed petitions, and the RJA appeared poised to empty death row. But a new Republican majority took power in 2012, and quickly defanged the RJA as well as legislating away the power of the state’s medical board to sanction doctors who presided over executions. The Department of Correction issued a new lethal injection protocol, though it’s not clear where they’ll get the drug they wish to use, since its Danish manufacturer refuses to sell it for use in executions. All in all, the future of the punishment remains unclear in the long term; in the short term, the stalemate will likely continue for some time. In the meantime, the desire to use death as punishment appears to have waned: Juries handed down no death sentences in 2012 and 2013 (though there has already been one death sentence in 2014). Nationally, support for death penalty has fallen, though it’s still at a healthy fifty-five percent. Perhaps more important, opposition has risen to nearly forty percent, meaning the US has gone from a nation that strongly favored capital punishment to one that shows both strong support and strong opposition to it. I published on the subject a few years back in an article entitled “The Racial Justice Act and the Long Struggle with Race and the Death Penalty in North Carolina.” I am at work right now on a book with Frank Baumgartner and Isaac Unah, integrating methodologies from political science and history, that will explore the issue from colonial North Carolina to the controversial present. Look for it in 2015.

Back Ways

A sign in rural Orange County designating the end of state maintenance.

Back Ways is a project exploring the social experience of segregation in the rural American South. It began with a rumor and a question. The rumor was this: that during the Jim Crow era in North Carolina, municipal authorities routinely removed roads in black neighborhoods from maintenance lists, meaning they would no longer benefit from formal upkeep. Roads leading to and from schools, churches, and general stores in these neighborhoods declined, and eventually the institutions and the people who relied on them disappeared as well. But at the same time, the residents of those areas seized those spaces as their own, using them as buffer zones between their neighborhoods and white-dominated towns.

The story itself reveals a compelling contest in the segregated South and also a tantalizing vision of what racial segregation looked like in spaces without “whites only” signs. Thus the question: what did segregation look like in the rural South?

To answer this question, my colleagues and I are conducting archival and oral history research with the eventual goal of mapping the roadways and back ways–alternative means of navigating potentially hostile environments–of Jim Crow North Carolina.

I am working on this project with Malinda Lowery, Professor of History and Director of the Southern Oral History Program, and Darius Scott, a graduate student in the Department of Geography. Take a look at Darius’s project blog here.

Media and the Movement

Media and the Movement is an oral history and digital preservation project that is exploring the legacies of the civil rights movement of the 1960s by conducting research about the intersection of media, journalism, and activism in the South in the 1960s, 1970s, and beyond. My colleague Joshua Davis and I are conducting oral history interviews and gathering archival radio and print material, aiming to unearth and preserve important voices from our recent past. Media and the Movement is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Read more about the project here.

The Civil Rights History Project

I served as Principal Investigator on the Civil Rights History Project, a nationwide oral history interviewing project that captured the recollections of 102 veterans of the civil rights movement, from Oakland to New York, Seattle to St. Augustine, Florida. The interviews will join the collection at the Library of Congress and will provide material for exhibitions at the Smithsonian’s newest museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The piece below offers a collective narrative of civil rights experiences.

These Were Real People from Southern Oral History Program on Vimeo.

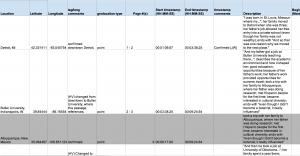

Locating Lynching

Inspired by the Equal Justice Initiative’s recent report on lynchings in the American South, this project seeks to locate and document lynchings in North Carolina using DH Press.

Begun in February of 2015 and powered by the bright young minds in the First Year Seminar Introduction to Digital Humanities, Locating Lynching aims to

- pinpoint, using latitude-longitude pairs, the locations of lynchings in North Carolina.

- provide access to relevant manuscript material, particularly digital newspaper articles.

- offer users both broad and specific information about lynching in North Carolina for research, teaching, and other uses.

- contribute to an important conversation about race, violence, and power in the United States.

White North Carolinians did not make their state a leader in lynchings, much to the relief of the state’s governors. But North Carolinians still lynched more than one hundred people between the late 1880s and 1960.

This project seeks to address the irony that despite the fact that members of lynch mobs documented their activities deliberately and prolifically, the physical spaces by and large remain unmarked. This project will visualize lynchings in new ways, privileging images of modern cites of historic lynchings over the mob-produced images of damaged black bodies that were intended to terrorize the wider black community.

Future iterations of the project will seek to integrate lynching and death penalty data (it is intriguing that Orange and Durham Counties had no reported lynchings, according to the EJI report, but among those counties with the most legal executions in the early 20th Century); address press coverage; and include attempted lynchings, not just those that resulted in a death. Visit the site.

Mapping the Long Women’s Movement: Activism in Appalachia

“Mapping the Long Women’s Movement: Activism in Appalachia” is a digital humanities project that makes use of the Digital Innovation Lab’s DH Press to explore Southern Oral History Program interviews with feminist activists in Appalachia. Since 2010, the SOHP has been pursuing the latest phase of its decade-long research initiative to study the “long civil rights movement,” the American civil rights movement reconceived as longer, deeper, broader, and more inclusive than commonly believed. The American civil rights movement was once defined as the struggle for racial equality during the late 1950s and 1960s, but that definition has been expanding in time and scope to include earlier eras and other freedom struggles. In particular, southern women’s feminist activism — their fight for economic, racial and gender justice – has recently begun to garner scholarly attention, whether these women thought of themselves as feminists or not. As SOHP researchers worked in the region, they learned that the life histories they were collecting were deeply informed by a sense of space: a family chasing jobs from state to state, women creating social services in a town without them, a community in Tennessee scattered by environmental degradation. As these women started consciousness-raising groups, formed community movements, or pursued individual social, racial, or economic justice agendas, Appalachian activists, organizers, and feminists created new spaces and connections between old spaces. Read more here.